A town. A slum. Fatal passion. And love.

A town. A slum.

Fatal passion. And love.

By Noel Morris

Maria de Buenos Aires is a show about a forgotten music, a forgotten dance, and a forgotten people. Cast in the gauzy hues of surrealistic poetry, the show explores the social conditions that gave rise to the tango. Not unlike hip-hop in our own country, the tango was a product of communities in distress. Initially dismissed as vulgar and immoral (dancing in an embrace was considered indecent), the tango followed an unlikely journey, traveling from the slums of Buenos Aires to the clubs of Paris. Only then, after it had become an international sensation, did it permeate Argentine society. After all, Argentinians knew the tango better than anyone—it had come from their society’s most undesirable places. The tango’s origins reach back to the 19th century when male workers, mostly from Germany and Italy, streamed into the Río de la Plata basin. Looking for jobs that didn’t exist, countless souls became mired in vast dockside slums already crowded with cowboys, or “gauchos,” and a large population of freed African slaves. With no opportunity, few women, and no means of escape, these communities became both a pressure cooker and melting pot. Music of different origins combined – including African rhythms, the waltz, the polka, and the habanera – to become the cultural expression of prostitutes and knife fighters. It wasn’t until the 1920s when the tango moved into the Argentine mainstream that it left behind its edgier associations. In their place grew a fervid sense of national pride. The tango became part of the Argentine identity, which proved stifling for young composer Astor Piazzolla.

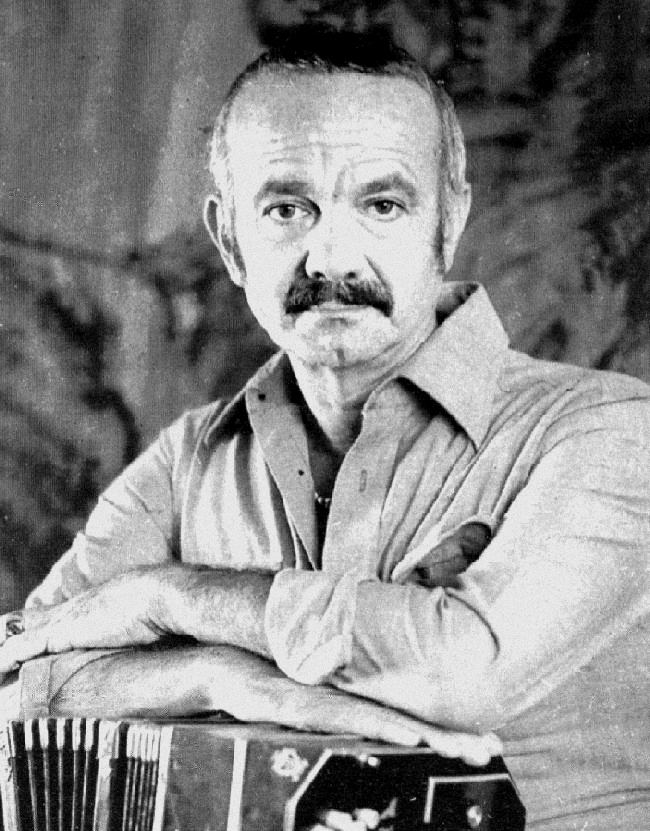

bandoneón, 1971

THE COMPOSER

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, no prophet is accepted in his hometown.” (Maria de Buenos Aires is filled with Christian imagery.) Similarly, the composer Astor Piazzolla, like the tango itself, was at first rebuffed by Argentine society. “Traditional tango listeners hated me,” he recalled. “All the tango critics and the radio stations of Buenos Aires called me a clown, they said my music was ‘paranoiac.’ And they made me popular. The young people who had lost interest in tango started listening to me. It was a war of one against all, but in ten years, the war was won.” Astor Piazzolla had spent much of his childhood in Manhattan. In 1929, thousands of miles from his native Argentina, the 8-year-old Piazzolla took up the bandoneón. Within two years, he made his first recording. At the same time, he began studying classical music with a Hungarian pianist. By the age of 17, he was living in Buenos Aires and playing bandoneón in one of Argentina’s most elite tango orchestras. Not surprisingly, he wasn’t ready to settle down. Through the 1940s, he explored both jazz and the music of Bartók and Stravinsky. At one point, he figured he was done with the bandoneón and the tango, but a move to Paris convinced him otherwise. At the age of 34, he turned up on the doorstep of the famed composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, and presented some of his “classical” compositions. Recounting their first meeting, Piazzolla described an awkward silence. Finally, when Boulanger spoke, her genius for cultivating musical talent became apparent: “I can’t find Piazzolla in this,” she told him. “You say that you are not a pianist. What instrument do you play, then?” “I didn’t want to tell her that I was a bandoneón player,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘Then she will throw me from the fourth floor.’ Finally, I confessed and she asked me to play some bars of a tango of my own. She suddenly opened her eyes, took my hand and told me: “You idiot, that’s Piazzolla!”

THE OPERITA

People often dismiss opera as an ivory tower art. In reality, composers have always absorbed the music of their environment—especially folk music—and filter it into their own works. Nevertheless, Astor Piazzolla is unique in that there is no daylight between him and his native music. When he folded classical and jazz elements into his writing, he pioneered what came to be known as tango nuevo. According to argentina-tango. com, “Astor Piazzolla lived and died as tango’s bad boy, having almost single-handedly invented the music’s vanguard.” Piazzolla completed María de Buenos Aires in 1968 using a libretto from writer, tango musician, and historian Horacio Ferrer. Swimming in surrealistic haze, Ferrer’s language touches upon then modern life (The Beatles and hippies), as well as things local to Buenos Aires. The words of this symbolist “operita” don’t completely make sense. But when the title character introduces herself, she tells you everything you need to know: “I am María of Buenos Aires. I am my town. María tango, slum María, María night, María fatal passion, María of love! Of Buenos Aires, that’s me!”

In each of these aspects (the town, the tango, the slum, the night, fatal passion, and love), the composer leans on Catholic imagery to craft a continuous cycle of life, death, and resurrection. In a sense, Maria de Buenos Aires is a Passion play. Maria “dies” each time she sells her body: “And I’ll still burn another life for two coins,” she sings. Halfway through the show, however, she really does die, only to persist in spirit form until she’s reborn at the end. Her resurrection does not point toward salvation, however. Rather, it is a commentary on the cycle of poverty. And with it comes a sense of inevitability and melancholy which, to this day, remain at the heart of the tango. “I sing a tango nobody ever sang, and I dream a dream nobody ever dreamt because tomorrow is today, and yesterday comes afterwards.”

THE BANDONEÓN

The bandoneón is essential to the sound of this genre of music. Throughout the golden age of the Argentine tango, the instrument was manufactured almost exclusively in Germany. Originally intended as a low-budget substitute for the church organ, it found its way to Argentina through a wave of German immigration. A type of concertina, the bandoneón has different sets of buttons for each hand. Each button produces two different pitches depending on whether the bellows are expanding or contracting.

THE GAUCHOS

The gaucho is a folk hero in Argentina – a skilled horseman and herdsman clad in a broad-brimmed hat, a poncho, and baggy trousers that are either cropped above the ankle or tucked into the boot. Working on the open range, the gauchos lived by a strict code emphasizing bravery, honor, and freedom—a code they upheld through skilled hand-to-hand combat called “esgrima criolla,” or Creole fencing. The gauchos’ weapon of choice was the dagger. When the gauchos were displaced by changes in land usage, many settled in the urban slums where the dagger, or facón, was shortened to fit beneath the lapel of the jacket. Some believe that tango moves show influence of knife fighters’ footwork.

THE DANCE

The embrace forms the basis of the tango. The upper body is meant to be relaxed and receptive to subtle cues from the partner. The feet hug the ground. In the early days, a man wouldn’t dream of stepping onto the dance floor with a woman before he had trained for months—or years—with other men. Given the extreme gender imbalance in Buenos Aires during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the tango’s embrace was said to help ease the loneliness of these disenfranchised people. In the slums, the tango became a type of courtship ritual between a john and a prostitute.

Maria de Buenos Aires | Mar. 28 – Apr. 7